The Historical significance of the Gardens by Catherine McDonald 2007

The McKay gardens are defined as an ‘industrial garden.’ Such gardens have been rare in Australia. Only two remain relatively intact: the Fletcher Jones Gardens in Warrnambool (1948) and the H.V. McKay Memorial Gardens (1909) (formerly the Sunshine Gardens) in Sunshine. Situated on approximately 2.3 hectares between the Sunshine residential estate and the former site of the Sunshine Harvester works, the McKay Gardens are both older and larger than the Fletcher Jones gardens and are arguably of greater historical significance.

In the mid 19th Century movements for social reform began to occur. The slums were not only considered noxious to the sensibilities of the growing middleclass but they were also a source of disease epidemics. Cholera outbreaks in London in the 1830s, galvanized the public hygiene movement to push for improved infrastructure, eventually resulting in the introduction of the Public Hygiene Act 1848. (UK) However, while “this had an effect on the planning and organization of central township areas, it had little impact on the teeming suburbs surrounding these areas.” It was not until some decades later that the issue of worker’s housing generally was directly addressed.

One of many reform responses to urban squalor was the development of the concept of the ‘garden suburb’. This concept is usually attributed to the theorist Ebenezer Howard. Howard argued that this concept would provide “a healthy, natural and economic combination of town and country life.” More socially utopian reformers sought to design and construct “model worker’s towns”. The most notable example was the industrialist W.H. Lever who founded Port Sunlight (UK) in 1888. Notably in this development, houses remained the property of the Lever company and workers continued to be tenants of the company. By the beginning of the 20th Century the concept of planned suburbs that provided infrastructure such as sewage and clean water and decent housing to workers, had become established but the implementation of this concept was still in its infancy.

Just as Britain endured the social impact of industrialization, our major cities also had their teeming slums for workers engaged in manufacturing industries. Like their British counterparts, these too were overcrowded and squalid. The defining characteristic of these suburbs was tiny housing allotments, narrow streets and the absence of infrastructure. Examples of these (now highly fashionable) narrow tenements still exist in many suburbs including Collingwood and Richmond.

Disease was also a constant threat. Smallpox epidemics in Sydney in the 1870s provided the impetus for a round of slum clearances and the first Public Health Act in 1896. But Melbourne did not begin to develop an effective sewage system for the city until 1889 and suffered reoccurring Typhoid epidemics. Life expectancy was low and infant morality rates were appalling. Eventually the public Hygiene Movement began to influence policy regarding the provision of basic infrastructure and Organized Labour was beginning to have an influence on the working conditions of the poor. Even so, the first systematic approaches to town planning did not occur until 1917.

We take the concept of a ‘garden suburb’ for granted now, but in the early 1900s the idea was still radically progressive. The layout of the Sunshine Residential Estate by H.V. McKay (1906-1909) was the first implementation of the concept in Australia, although its impetus may have owed as much to the concept of ‘model workers’ towns’ as did to the theories of Ebenezer Howard. Certainly, other early and notable Australian examples of the ‘garden suburb’ did not commence until 1912 in the case of Daceyville (Sydney) and 1917 in the case of Colonel Light Gardens (Adelaide) respectively.

As in the Port Sunlight experiment, McKay sought to provide housing for his workers close to their place employment but in circumstances that recognized the right to decent housing. The Sunshine Estate was laid out in large housing allotments and wide tree lined streets often planted with native gums, representing an allegiance to the new Federation. It was also provided with infrastructure such as water and sewage. The Estate also demonstrated an Australian “preference for detached, single story dwellings”, producing a lower density of housing than in the UK equivalents. Importantly, and unlike the Port Sunlight estate, McKay encouraged his workers to buy the land and to build their own housing. Workers were no longer exclusively tenants of the industrialist.

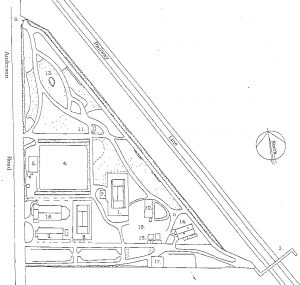

The Sunshine Gardens were a key component of McKay’s concept for a livable environment “gardens, parks, bowling greens and so forth have an uplifting influence on the people, and make them feel more satisfied than they are when the surroundings of their homes are dull and unattractive”. They were strategically situated “on a flat triangular site, bounded by the Melbourne to Bendigo Railway line, Anderson Road and Chaplin Reserve” between the housing estate and the factory complex. While the Gardens were designed primarily as a convenience for workers of the McKay Harvester Factory, the position of the gardens also emphasized the new social philosophy. Workers were no longer mere extensions of the industrialist’s manufacturing process but were recognized as having lives of their own. This was manifest by their private residences being separated from the factory by open, civic space. This spatial relationship between the housing estate and the industrial estate is still discernible although the Harvester factory has since been demolished.

The historical significance of the gardens rests upon more than their mere existence. Private gardens are an important means of self-expression, but the design and layout of public gardens represent an expression of the community’s cultural character as well as its hopes and aspirations. The original design and layout of the H.V. McKay gardens is therefore also significant, revealing the character of the community that developed the gardens. Originally, the layout of the gardens consisted of sweeping curved paths, large shrub and flower beds with annual floral displays and specimen trees planted in green lawn areas. This style of garden design is known as ‘gardeneseque’ and is a characteristic of many of Melbourne’s most notable public gardens including the Fitzroy Gardens.

The term ‘gardenesque’ is attributed to John Claudius Loudon and dates from 1832. It refers to a style of gardening that is clearly recognizable as a work of art created by a designer rather than merely a continuation of nature. Not only is this style of garden design aesthetically pleasing in its own right, but the style can also be seen as another response to the pressures of industrialization. On the one hand, the use of curves and flowing forms can be seen as a renewed appreciation of natural landscape threatened by industrialization. It represented a nostalgia for a idyllic pastoral past that had been overwhelmed by urbanization. On the other hand, the appeal to artifice; a landscape that was clearly designed, manifest a desire for a control over the natural environment while the use of exotic specimens appealed to the desire for novelty and an interest in new that was characteristic of the Edwardian age. As a specific response to the cultural environment, the choice of gardenesque design for the gardens demonstrated an optimistic view of the future in which the relationship between man and the environment, both industrial and natural, could be managed in a ‘civilized’ way.

Australian gardeners of this period were inventive and adaptable, adopting the use of plants that were suitable for the environment in which they found themselves. The natural environment of the gardens is the flat volcanic planes of Western Melbourne, exposed to strong winds and subject to both frosts and drought. The gardeners responded to this challenge by planting a broken hedge along Anderson Road of Pittosporum to provide shelter from the westerly winds, while an informal hedge of mixed shrubs including Pittosporum, Hawthorn and Pomegranates along the railway line provided shelter from northerly winds. These species are tough, drought and frost resistant and provided ideal species for wind breaks. Similarly, the species used for massed flower beds of perennials included Ageratum, zinnias, bonfire, salvia and celosia. Not only did these provide spectacular and colorful displays, but after many decades of being unfashionable, some of these species have become fashionable again as part of the ‘water wise’ approach to gardening. The choice of structural species reflected a practicality and resilience as well as a cheerful sense of being at ease in the Australian environment.

The layout and choice of construction material for paths was also significant. These reflected the gardenesque preference of curves and flowing lines and were also positioned to provide visual interest within the gardens for pedestrians. A straight path known as the ‘straight six’ located along the railway line boundary and one along the east west boundary provided counterpoints to a number of curving paths within the internal space of the garden. These partially concealed elements of the overall design of the garden, providing variation of interest and a sense of discovery. One notable element of the path running east west across the gardens, was a high curved Cypress hedge with park bench within the curve. This was an uncommon horticultural ‘folly’. Just as with the botanic elements of the structural plan, the paths also demonstrated an adaptation to the local environment. The paths were made of a golden or yellow colored gravel known as ‘salamander’, quarried in the local area. This provided both color and textual contrast to the green of the lawns. However, it was also practical, providing a durable surface under conditions that range from sweltering in the summer to bogey clay in the winter. It also provided excellent drainage and reduced glare in summer.

Along with the structural plantings, the McKay gardens were once notable for their annual floral displays. These displays where a yearly attraction for visitors from throughout the state and were an important source of local community pride. Unlike the structural plantings, the annual floral displays required a considerable amount of effort, including additional water and labor intensive weeding and bed preparation. A sense of invention and development was evident in these floral displays, the gardens being especially known for the development and breeding of dahlias and chrysanthemums. Numerous cultivars were developed at the gardens particularly during the period of 1927-52 under the stewardship of the head gardener Harold Gray. The names of the cultivars often reflected local associations. For instance, one cultivar was named ‘Harold Gray’, another ‘Margaret’ after the gardener’s wife and yet another was called ‘Sunshine’. However, others had larger social associations such as Coronation Pink named in honour of the English Queen’s coronation and Bardia, possibly named after the first battle of World War Two. The annual floral displays were planted in wide flower beds along the straight six pathway and in large round flower beds in the lawn areas.

Catherine McDonald 2007